Leaving Earth’s gravity transforms more than your body, it transforms what awareness itself can be.

Note: This article is for educational and informational purposes only. See full disclaimer at the end.

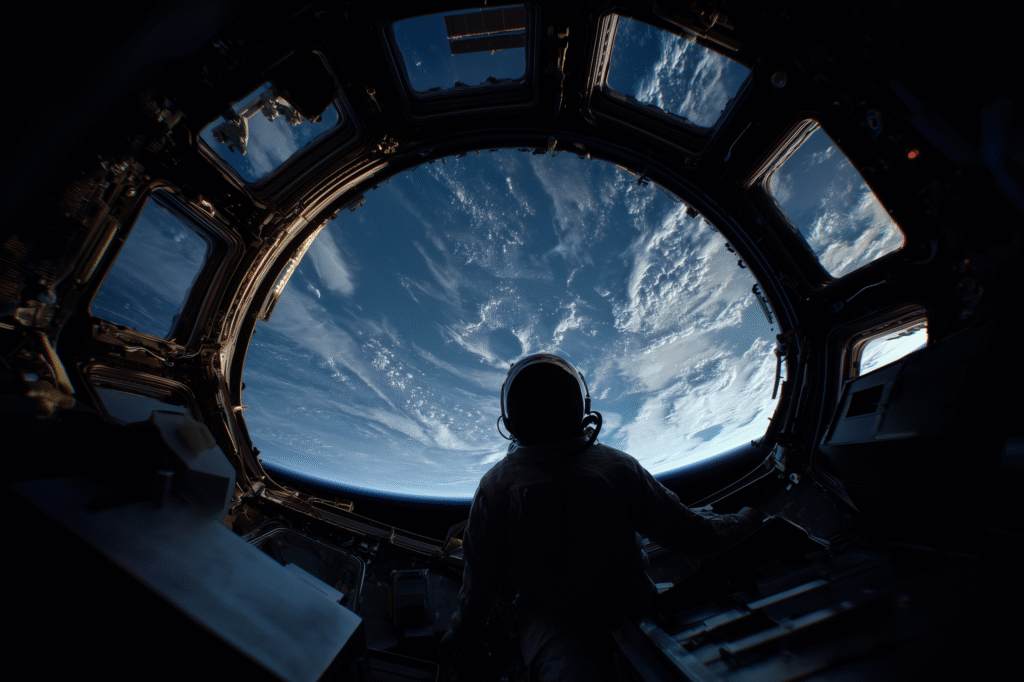

What happens to consciousness when you’re floating 400 kilometers above the only home humanity has ever known, watching sixteen sunrises a day while your brain literally reshapes itself in ways that take years to reverse?

This isn’t philosophy class speculation. This is the documented reality of what happens when human consciousness leaves Earth.

The Moment Everything Changes

Apollo 8 astronaut William Anders captured more than a photograph when he turned his camera toward Earth on December 24, 1968. He captured a cognitive revolution. “We came all this way to explore the Moon,” he later reflected, “and the most important thing is that we discovered the Earth” [1].

Author Frank White coined the term “Overview Effect” in 1987 to describe this profound shift in awareness experienced by astronauts viewing Earth from space [2]. Researchers characterize it as “a state of awe with self-transcendent qualities, precipitated by a particularly striking visual stimulus” [2]. But this clinical description barely captures what astronauts describe: spontaneous epiphany experiences, interconnected euphoria, instant global consciousness [3].

Apollo 14 astronaut Edgar Mitchell described it with striking precision: “You develop an instant global consciousness, a people orientation, an intense dissatisfaction with the state of the world, and a compulsion to do something about it” [3]. Gene Cernan felt “too much purpose, too much logic” in what he witnessed, leading him toward spiritual conclusions he hadn’t anticipated [3].

This isn’t universal—not all astronauts experience it the same way, and cultural backgrounds influence how the effect manifests and is interpreted [2]. But the phenomenon occurs frequently enough, and with sufficient consistency, that it demands explanation beyond poetic enthusiasm.

Research examining astronaut experiences found that viewing Earth from space triggers intense emotional reactions that change perspectives on humanity’s place in the universe [4]. Many astronauts no longer identify with specific nationalities after spaceflight, instead seeing themselves and all Earth citizens as one people on one world [4].

What Space Actually Does to Your Brain

While astronauts describe transcendent experiences, neuroscientists document something more tangible: physical restructuring of brain tissue in microgravity.

The changes are dramatic. Brain ventricles—hollow cavities filled with cerebrospinal fluid—expand by up to 25% in microgravity [5]. Research published in Scientific Reports found that astronauts spending six months or more on the International Space Station showed ventricular expansion that recovered only 55-64% toward pre-flight size after six to seven months back on Earth [6].

The implications are startling: these structural changes persist for approximately three years [5]. Your brain essentially needs three years to fully recover its elasticity after six months in space.

But duration matters in unexpected ways. Ventricular expansion appears to level off after about a year in microgravity, suggesting the brain reaches a new equilibrium rather than continuing to expand indefinitely [6]. This offers cautious optimism for Mars missions: while the journey fundamentally alters brain structure, the changes may plateau rather than compound.

Studies using magnetic resonance imaging reveal widespread alterations in gray and white matter, changes in brain tissue microstructure and connectivity, and shifts in how the brain processes vestibular, visual, motor, and cognitive information [7]. Research documented significant impacts on sensorimotor cortex and changes in alpha and mu oscillations recorded in astronauts [8].

The brain literally rewires itself in response to the absence of gravity—a demonstration of neuroplasticity operating under the most extreme environmental conditions humans have ever experienced.

The Psychological Architecture of Isolation

Physical brain changes tell only part of the story. The psychological experience of off-planet existence presents challenges that go beyond altered cerebrospinal fluid distribution.

NASA research identifies prolonged isolation and confinement as significant risk factors for behavioral issues and psychiatric disorders, including anxiety and depression [9]. These factors impact sleep, morale, and decision-making—all critical for mission success and crew safety [9].

Current International Space Station astronauts can routinely connect with family and medical professionals. But deep space missions will introduce communication delays measured in minutes, not milliseconds. A Mars expedition would experience up to 30-minute delays each way, making real-time psychological support impossible [10].

Studies of cosmonauts and astronauts reveal patterns: psychological closing (filtering what crew members communicate to ground control), autonomization (crew members becoming more egocentric), and displacement of tension from crew to mission control personnel [11]. Research examining possible psychological challenges for Mars expeditions highlighted isolation and monotony, distance-related communication delays, leadership issues, and cultural misunderstandings within international crews as primary concerns [11].

Yet here’s the paradox: while under two percent of medical issues on shuttle missions between 1981 and 1998 were behavioral health-related, many astronauts describe spaceflight as “a mental high” [12]. The experience overall is one of intense pressure that many find exhilarating rather than debilitating [12].

Canadian astronaut David Saint-Jacques captured this complexity: “You’re very, very far away from the people you love on Earth and that can make you sad perhaps” [13]. The acknowledgment matters. For decades, NASA’s “Right Stuff” culture discouraged astronauts from reporting psychological difficulties, fearing it indicated weakness [12]. The Canadian Space Agency’s partnership with museums to create exhibits on mental health challenges represents a significant cultural shift toward transparency about the psychological costs of space exploration [13].

The Consciousness Implications

So what do these combined effects—Overview Effect experiences, structural brain changes, psychological adaptation to isolation—tell us about consciousness itself?

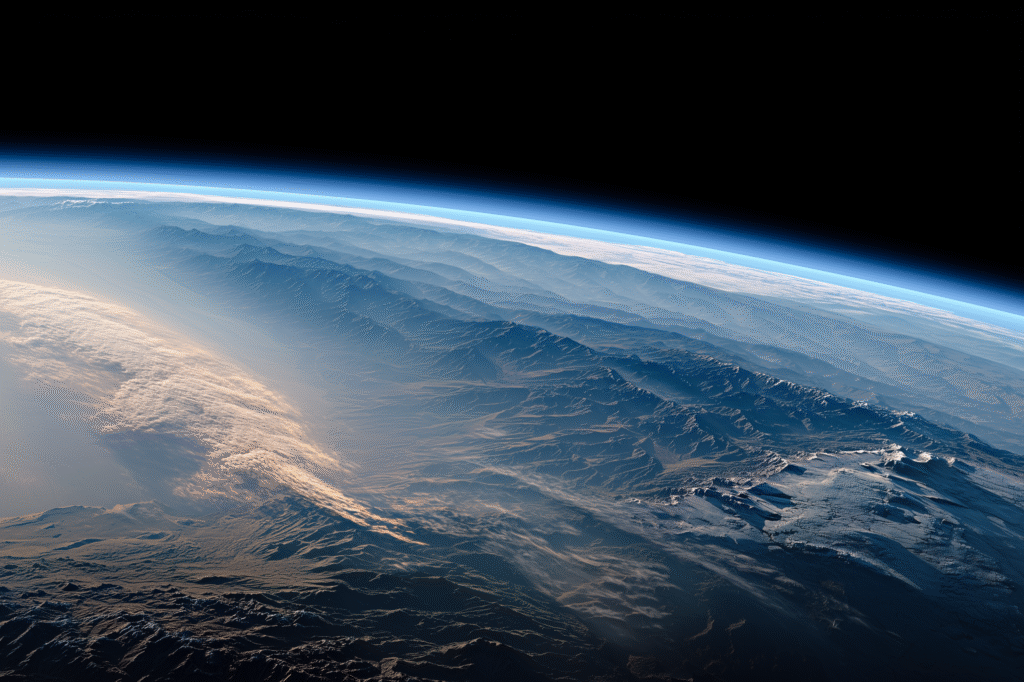

First, they reveal consciousness as profoundly context-dependent. The shift from “here” to “there” when viewing Earth from space isn’t merely perceptual but existential. Borders vanish. The paper-thin atmosphere protecting everything you’ve ever known becomes viscerally apparent. The deadly vacuum of space surrounding this “tiny, fragile ball of life” becomes undeniable reality rather than abstract knowledge [2].

From orbit, astronauts see a world without borders. They see unity where surface-dwellers see division [14]. This isn’t naive idealism—it’s unavoidable perception. The lines humans draw on maps simply don’t exist from 400 kilometers up.

Second, these changes suggest consciousness operates through biological mechanisms that are themselves malleable. Your brain physically restructures in response to environmental demands. The neural networks processing vestibular information, spatial orientation, and self-motion perception undergo dramatic reorganization [7]. The substrate of consciousness—the physical brain—adapts to radically different conditions, and with it, conscious experience transforms.

Third, the psychological responses to isolation and confinement reveal how deeply social our consciousness is. The phenomenon of “psychological closing”—filtering communications and becoming more egocentric in isolated environments [11]—suggests that normal consciousness depends on continuous connection with others. Remove that connection, and consciousness itself shifts.

Becoming a Multiplanetary Species

These insights carry profound implications as humanity contemplates becoming a multiplanetary species.

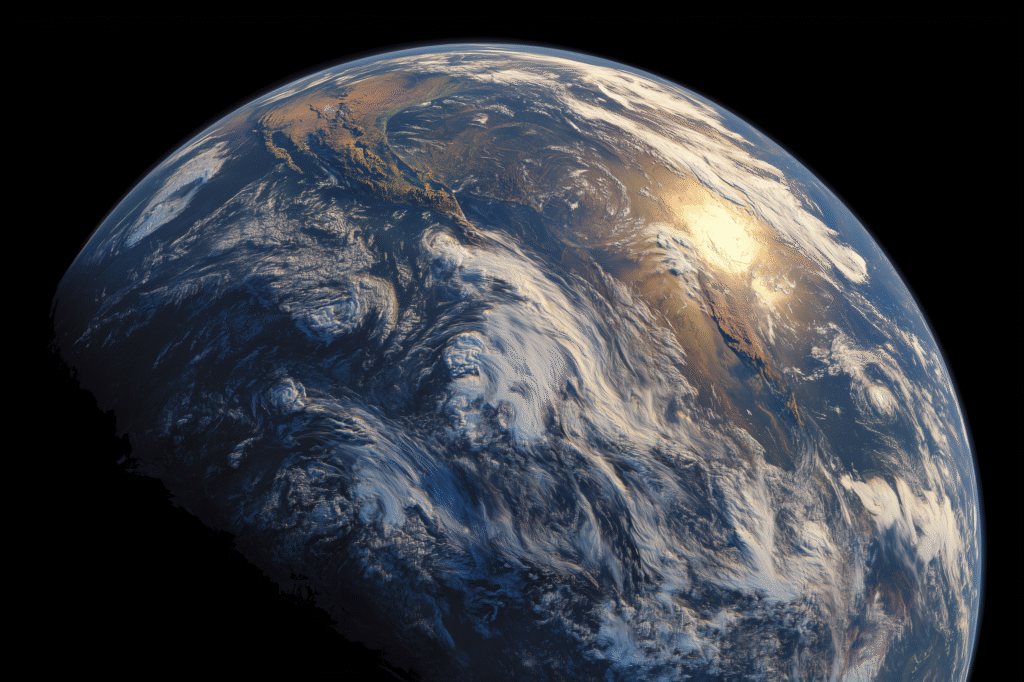

If six months in low Earth orbit—where you can still see Earth filling most of your field of view—produces consciousness changes that persist for years, what happens during a three-year Mars mission where Earth becomes barely visible?

Canadian Space Agency researchers pose this question directly: “Will they feel lonelier? Will they feel completely disconnected to Earth?” [14]. The Overview Effect is most powerful when viewing Earth from relatively close proximity. Frank White distinguished between experiences in low Earth orbit—where the planet dominates your view—and seeing the whole Earth against the backdrop of cosmos from the Moon, describing it as “a big difference” [2].

From Mars, Earth appears as a point of light. The psychological impact remains unknown. Does consciousness of home attenuate with distance? Does the Overview Effect reverse, creating instead a profound sense of cosmic isolation?

Perhaps more fundamentally: what does it mean to be human when the defining context of human consciousness—Earth’s gravity, Earth’s visual presence, Earth’s immediate accessibility—no longer applies?

This isn’t abstract philosophy. Mars settlers will develop different neural structures. Their brains will adapt to 38% of Earth’s gravity in ways we can’t currently predict [11]. Their conscious experience will be shaped by Martian sunrises, Martian landscapes, Martian isolation. After generations, will Martian-born humans experience consciousness differently than Earth-born humans?

The Expansion of Awareness

Here’s what makes this moment in human history unprecedented: we’re now aware of what leaving our planet does to consciousness. We have data. We have neuroimaging studies showing structural brain changes. We have astronaut testimonies describing cognitive shifts. We have psychological research documenting isolation effects.

Previous generations of explorers couldn’t study themselves this way. No Polynesian navigator crossing the Pacific could undergo pre- and post-voyage brain scans. No European explorer reaching the Americas could document their psychological changes with standardized assessment tools.

We can.

And what we’re learning is that consciousness—whatever it ultimately is—exists in dynamic relationship with its environment. Change the environment drastically enough, and consciousness changes with it. Not just what you’re conscious of, but how consciousness operates, how it’s structured, what neural patterns support it.

Some changes appear maladaptive. The sensorimotor impairment astronauts experience upon returning to Earth, the vestibular processing alterations, the difficulty readapting to gravity [8]—these suggest limits to how far consciousness can stretch from its evolutionary home without cost.

Other changes appear adaptive. The neuroplasticity enabling brains to reorganize in microgravity, the psychological resilience many astronauts demonstrate, the capacity to function effectively in environments that would have killed our ancestors within minutes [7]—these suggest consciousness possesses remarkable flexibility.

But perhaps the most significant change is the shift in perspective itself. Seeing Earth from outside fundamentally alters how you understand your place in existence. The Overview Effect produces what Edgar Mitchell called “savikalpa samadhi”—a state where “you see things as you see them with your eyes, but you experience them emotionally and viscerally, as with ecstasy, and a sense of total unity and oneness” [3].

This isn’t just about space. It’s about recognizing that consciousness itself has horizons—and those horizons can expand.

Your Consciousness, Wherever It Goes

You’ll likely never float in microgravity watching Earth rotate beneath you. The experience remains, for now, extraordinarily rare. Only about 600 humans have been to space in all of history.

But the insights from space consciousness research apply more broadly.

Consciousness adapts to environment. Your brain physically reorganizes based on context. Your awareness shifts based on perspective. These truths hold whether you’re in microgravity or commuting to work.

The Overview Effect demonstrates that dramatic shifts in physical perspective can produce equally dramatic shifts in conscious experience and values. From space, astronaut Ron Garan saw Earth as “this really beautiful oasis out in the middle of nothingness” [1]. That perception changed how he understood human conflicts, environmental challenges, the arbitrary nature of national boundaries.

You don’t need space travel to shift perspective. You need willingness to step outside habitual contexts and see from different vantage points. The mechanism is the same even if the magnitude differs.

The space psychology research reveals how isolation affects consciousness. Psychological closing, autonomization, displacement of tension [11]—these patterns emerge in extreme isolation but exist in milder forms in everyday disconnection. Understanding how consciousness changes under isolation helps recognize when you’re filtering communications, becoming egocentric, displacing tensions onto others.

The neuroscience showing brain plasticity in microgravity demonstrates that your neural architecture continuously adapts. This happens on Earth too, just more slowly and subtly. Every new skill, every changed habit, every shifted perspective involves physical reorganization of brain tissue. You’re not stuck with the consciousness you have. The substrate itself remains malleable.

The Future of Human Awareness

As more humans venture into space—as missions extend beyond low Earth orbit, as settlements establish on the Moon and Mars, as the first children are born off-world—we’ll learn much more about consciousness than we currently know.

We’ll discover how consciousness develops in reduced gravity. We’ll understand how distance from Earth affects psychological well-being. We’ll see whether generations born on Mars develop fundamentally different modes of awareness.

But we don’t need to wait for that future to recognize what current space research already shows: consciousness is not a fixed property but an adaptive process. It exists in relationship with environment, shaped by context, capable of transformation when conditions change sufficiently.

The astronauts floating above us, experiencing brain restructuring and cognitive shifts while watching Earth turn beneath them, are pioneers of consciousness as much as pioneers of space.

They’re showing us what awareness can become when liberated from the gravitational and perceptual constraints that shaped its evolution.

And in doing so, they’re expanding the horizon of what’s possible for consciousness itself.

See you in the next insight.

Comprehensive Medical Disclaimer: The insights, frameworks, and recommendations shared in this article are for educational and informational purposes only. They represent a synthesis of research, technology applications, and personal optimization strategies, not medical advice. Individual health needs vary significantly, and what works for one person may not be appropriate for another. Always consult with qualified healthcare professionals before making any significant changes to your lifestyle, nutrition, exercise routine, supplement regimen, or medical treatments. This content does not replace professional medical diagnosis, treatment, or care. If you have specific health concerns or conditions, seek guidance from licensed healthcare practitioners familiar with your individual circumstances.

References

The references below are organized by study type. Peer-reviewed research provides the primary evidence base, while systematic reviews synthesize findings.

Peer-Reviewed / Academic Sources

- [1] Yaden, D. B., et al. (2016). Spirituality, humanism, and the Overview Effect during manned space missions. ScienceDirect. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0094576518305514

- [2] Seidler, R. D., et al. (2023). Impacts of spaceflight experience on human brain structure. Scientific Reports. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-023-33331-8

- [3] Hupfeld, K. E., et al. (2024). Effect of spaceflight experience on human brain structure, microstructure, and function: systematic review of neuroimaging studies. PMC. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11582179/

- [4] McGregor, H. R., et al. (2022). Microgravity effects on the human brain and behavior: Dysfunction and adaptive plasticity. PMC. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9650717/

- [5] Smith, N., et al. (2023). Supporting the Mind in Space: Psychological Tools for Long-Duration Missions. PMC. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11499714/

- [6] Caddick, Z. A., et al. (2021). The Burden of Space Exploration on the Mental Health of Astronauts: A Narrative Review. PMC. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8696290/

Government / Institutional Sources

- [7] NASA. (2025). Risk of behavioral conditions and psychiatric disorders. https://www.nasa.gov/reference/risk-of-behavioral-conditions-and-psychiatric-disorders/

- [8] Canadian Space Agency. (n.d.). The Overview Effect. https://www.asc-csa.gc.ca/eng/youth-educators/toolkits/mental-health-and-isolation/overview-effect.asp

Industry / Technology Sources

- [9] Geography Realm. (2024). Overview Effect: Quotes from Astronauts After Seeing the Earth from Space. https://www.geographyrealm.com/overview-effect-quotes-from-astronauts/

- [10] Wikipedia. (2025). Overview effect. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Overview_effect

- [11] Quartz. (2022). Astronauts report an “overview effect” from the awe of space travel—and you can replicate it here on Earth. https://qz.com/496201/astronauts-report-an-overview-effect-from-the-awe-of-space-travel-and-you-can-replicate-it-here-on-earth

- [12] Brainfacts.org. (2024). Six Months in Space Changes Your Brain for Years. https://www.brainfacts.org/neuroscience-in-society/tech-and-the-brain/2024/six-months-in-space-changes-your-brain-for-years-011724

- [13] Wikipedia. (2025). Psychological and sociological effects of spaceflight. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Psychological_and_sociological_effects_of_spaceflight

- [14] MIT CMSW. (2019). Headspace: How Space Travel Affects Astronaut Mental Health. https://cmsw.mit.edu/angles/2019/headspace-how-space-travel-affects-astronaut-mental-health/

- [15] Psychology Today. (2019). Astronauts Open Up About Depression and Isolation in Space. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/home-in-the-cosmos/201902/astronauts-open-about-depression-and-isolation-in-space