The most dangerous health decision isn’t what you do—it’s what you don’t do.

Note: This article is for educational and informational purposes only. See full disclaimer at the end.

You know you should schedule that check-up. You’ve been meaning to call the doctor for weeks—maybe months. Yet somehow, the call never gets made. Sound familiar?

You’re not alone, and you’re not lazy. You’ve fallen into what psychologists call the avoidance trap—a pattern so common that research shows 41% of adults delay medical care, even when they know it’s important [1].

This isn’t about laziness or poor planning—it’s about the deeper psychology of avoidance and how our brains are wired to postpone discomfort, even when waiting creates far greater problems.

The Avoidance Pattern

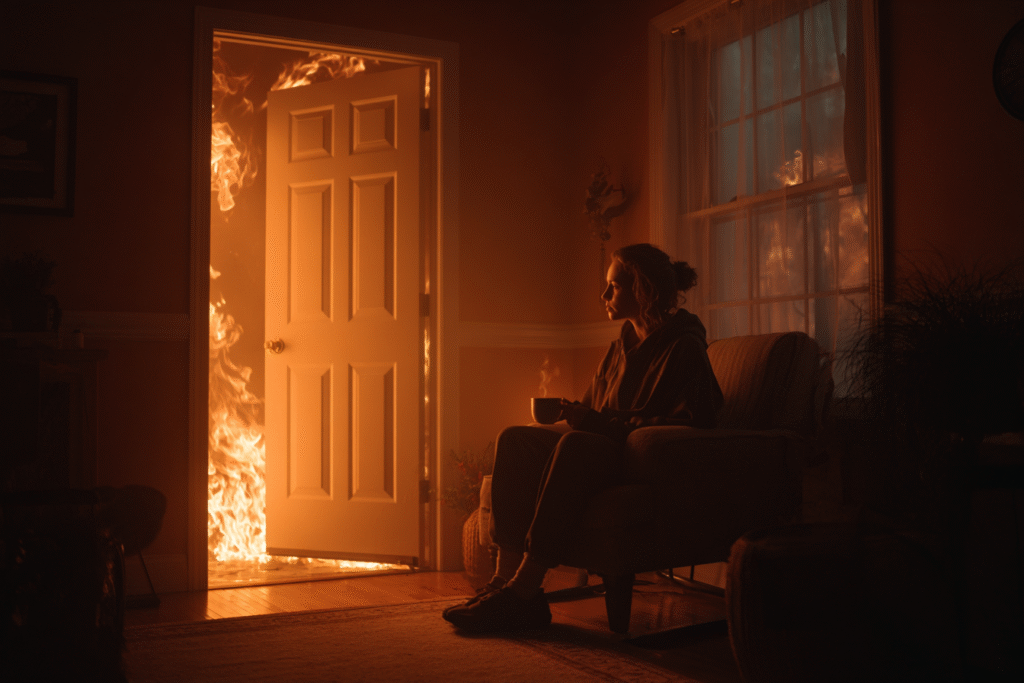

Here’s what makes health avoidance particularly insidious: the very mechanism designed to protect us from immediate emotional discomfort actually increases our long-term risk.

When we avoid health-related tasks, we experience temporary relief—our stress drops, anxiety decreases, and we feel better in the moment [2].

This immediate reward reinforces the avoidance behavior, making it more likely we’ll repeat the pattern. Health avoidance is driven not by time mismanagement but by fear and emotional regulation [3].

And because it works in the short term, we repeat it.

It’s a psychological defense mechanism that prioritizes short-term emotional comfort over long-term health outcomes.

The Four Mechanisms of Health Avoidance

Health avoidance isn’t random—it follows predictable patterns. Once you recognize these four core mechanisms, you can spot them operating in your own life and begin to interrupt the cycle.

1. The Fear Amplification Cycle

The fear-avoidance model, originally developed to understand chronic pain, explains how fear-based thinking creates self-perpetuating cycles of avoidance [4]. When we catastrophize potential health outcomes—imagining the worst-case scenarios—our brains interpret medical appointments as threats requiring defensive action.

This fear amplification works through what neuroscientists call temporal discounting [5]. Our brains naturally devalue future consequences in favor of immediate rewards. The abstract concept of “better health later” loses out to the concrete reality of “avoiding anxiety now.”

2. The Emotional Overwhelm Factor

Health decisions often involve complex emotional terrain: vulnerability, mortality awareness, loss of control, and confronting our physical limitations. Unlike other types of procrastination, health avoidance carries existential weight [6]. We’re not just postponing a task; we’re postponing confrontation with our own mortality and fragility.

Research on anxiety sensitivity—the fear of anxiety symptoms themselves—shows how this creates compounding avoidance [7]. People begin avoiding not just medical appointments, but even thinking about health, creating what psychologists call experiential avoidance.

3. The Control Illusion

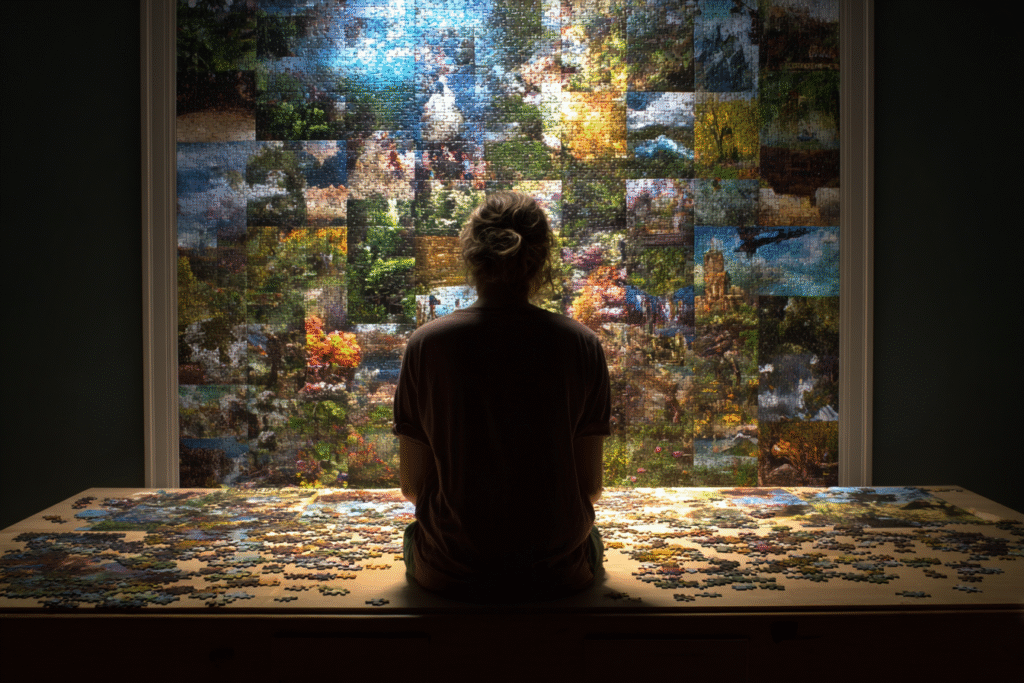

One of the most counterintuitive aspects of health avoidance is that it gives us a false sense of control. By not seeking medical attention, we maintain the illusion that we’re controlling our health narrative [8].

Schrödinger’s medical test—if we don’t take it, we can exist in a state where nothing is definitively wrong.

As long as the test hasn’t been run, we’re both healthy and not. It keeps us in a false certainty bubble.

This illusion is psychologically protective but practically dangerous. Many believe they’re “managing” their health by avoiding confirmation of problems [9].

They’re often wrong.

4. The Expertise Intimidation Effect

Healthcare systems, despite good intentions, can inadvertently create psychological barriers through their complexity and authority dynamics [10]. Many people experience what researchers call “medical anxiety”—a specific form of performance anxiety related to medical settings and interactions with healthcare providers.

This intimidation effect is particularly pronounced among intelligent, successful people who are accustomed to competence in other areas of life. The vulnerability required in medical settings can feel especially uncomfortable for those who typically occupy expert roles themselves.

The Neuroscience of Avoidance

Understanding what happens in your brain during health avoidance can help break the cycle. Neuroimaging studies reveal a conflict between two brain systems: the limbic system (emotional processing) and the prefrontal cortex (rational planning) [5].

A third key player—the anterior cingulate cortex—detects this internal conflict. It registers the tension between intention (“I should call”) and inhibition (“I don’t want to know”), creating a state of internal friction that primes us for avoidance.

When you think about calling the doctor, your amygdala—the brain’s alarm system—activates in response to perceived threat. This triggers stress hormones that create the familiar feelings of anxiety and dread. Your prefrontal cortex knows rationally that the appointment is important, but the emotional intensity of the limbic response often wins.

The brain’s reward system then reinforces avoidance by providing immediate relief when you postpone the decision. This creates what neuroscientists call an “avoidance learning cycle“—your brain literally learns that avoiding health decisions reduces stress.

It’s like hitting snooze on an alarm that controls your health.

Each delay offers temporary peace—but the real danger quietly builds while you sleep through the warning.

The True Cost of Waiting

The economic data on health avoidance reveals staggering costs, both personal and societal. Direct healthcare costs associated with delayed care include:

- Emergency interventions: Conditions manageable with basic preventive care often escalate into expensive emergencies when delayed [11]

- Advanced disease management: Early-stage conditions are far cheaper to treat than advanced ones [12]

- Medication complexity: Delayed care often leads to more complex medications and higher drug costs [13]

But the hidden costs extend far beyond medical bills:

Productivity impact: Untreated health conditions reduce focus, increase absenteeism, and quietly drain performance [13]. The Australian Productivity Commission estimated that improving health in people with fair or poor health could increase GDP by $4 billion annually.

Relationship strain: Health anxiety and untreated conditions create stress that affects family relationships and social connections [2]. The emotional burden of carrying unaddressed health concerns impacts not just the individual but their entire support network.

Quality of life degradation: Perhaps most significantly, health avoidance steals time from the life you want to live. Energy spent managing anxiety about potential health problems is energy not available for pursuing goals, relationships, and experiences.

Cascade effects: Delayed health care often creates cascading problems—one untreated condition leads to secondary complications, which require more complex and expensive interventions [14].

And once that time is gone, no intervention can buy it back.

The Intervention Psychology

Breaking the avoidance cycle requires understanding its psychological mechanics rather than relying on willpower alone. Research identifies several evidence-based approaches:

Emotional Regulation First

Since health avoidance is fundamentally about emotional regulation, addressing the underlying anxiety is often more effective than focusing on the avoided behavior itself [2]. Techniques like mindfulness, cognitive restructuring, and gradual exposure can reduce the emotional intensity that drives avoidance.

Implementation Intentions

Research on procrastination shows that “implementation intentions”—specific if-then plans—can bypass the emotional resistance that derails good intentions [3].

Instead of “I should call the doctor,” try “If it’s Tuesday morning after my coffee, then I will call the doctor’s office.”

You can also plan for emotional resistance:

“If I start feeling anxious before calling, I’ll take three deep breaths and remind myself that clarity is more empowering than avoidance.”

Social Accountability

The presence of others can override individual avoidance tendencies [15]. Telling someone about your intention to schedule medical care, or having them accompany you, can provide the external motivation that internal motivation lacks.

When others are involved, we borrow their courage when ours is low.

Cognitive Reframing

Shifting focus from what you’re trying to avoid to what you’re trying to achieve can reduce psychological resistance [16]. Frame medical appointments as investments in the life you want to live rather than confrontations with problems you want to avoid.

Avoidance protects your present discomfort. Reframing protects your future self.

The Foundations of Health Ownership

The goal isn’t to eliminate all health-related anxiety—some concern about health is adaptive and motivating. Instead, the goal is to prevent anxiety from becoming a barrier to appropriate care.

This requires developing what researchers call “health self-efficacy“—confidence in your ability to navigate health decisions and manage health-related challenges [17].

Key components include:

Health literacy: Understanding how healthcare systems work reduces anxiety and increases confidence in navigating medical appointments and decisions.

Emotional awareness: Recognizing when anxiety is driving avoidance allows you to address the emotional component rather than fighting against it.

Systems thinking: Understanding that your current health is an investment in your future health helps motivation overcome momentary discomfort.

Partnership mindset: Viewing healthcare providers as partners rather than authorities reduces the intimidation factor that drives avoidance.

The Proactive Advantage

The research on preventive care versus crisis intervention reveals a profound truth: almost every health intervention is more effective, less expensive, and less emotionally demanding when implemented early [18].

Resilience isn’t the absence of illness—it’s the presence of readiness

Proactive health ownership transforms your relationship with medical care from reactive crisis management to ongoing optimization.

This shift has psychological benefits beyond physical health: it reduces health-related anxiety, increases sense of control, and frees mental energy for other pursuits.

Moving Beyond the Trap

Health avoidance is a normal human response to uncertainty and vulnerability.

Understanding its psychology doesn’t eliminate it but does provide tools for managing it more effectively. The goal is progress, not perfection—each step toward proactive health engagement builds momentum for the next.

Remember: the temporary discomfort of scheduling that appointment is always less than the prolonged anxiety of avoiding it.

Your future self isn’t waiting for perfection—just your next small act of courage.

Looking Forward

In the next insight, we’ll break down the actual costs of waiting—dollars lost, relationships strained, and time wasted—and begin mapping a proactive system that puts your health back in your hands.

What would shift if you faced it now, not later?

What’s the one call, appointment, or decision your future self is quietly begging you to make?

The avoidance trap is powerful, but it’s not permanent. Understanding its mechanisms is the first step toward freedom.

See you in the next insight.

Comprehensive Medical Disclaimer: The insights, frameworks, and recommendations shared in this article are for educational and informational purposes only. They represent a synthesis of research, technology applications, and personal optimization strategies, not medical advice. Individual health needs vary significantly, and what works for one person may not be appropriate for another. Always consult with qualified healthcare professionals before making any significant changes to your lifestyle, nutrition, exercise routine, supplement regimen, or medical treatments. This content does not replace professional medical diagnosis, treatment, or care. If you have specific health concerns or conditions, seek guidance from licensed healthcare practitioners familiar with your individual circumstances.

References

The references below are organized by study type. Peer-reviewed research provides the primary evidence base, while systematic reviews synthesize findings across multiple studies for broader perspective.

Peer-Reviewed / Academic Sources

- [1] Czeisler, M. É., et al. (2020). Delay or Avoidance of Medical Care Because of COVID-19-Related Concerns. MMWR, 69(36), 1250-1257. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6936a4.htm

- [2] Sirois, F. M. (2023). Procrastination and Stress: A Conceptual Review of Why Context Matters. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(6), 5031. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10049005/

- [3] Sirois, F. M. (2023). Procrastination and Stress: A Conceptual Review of Why Context Matters. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(6), 5031. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10049005/

- [4] Vlaeyen, J. W., & Linton, S. J. (2012). Fear-avoidance model of chronic pain: the next generation. Clinical Journal of Pain, 28(6), 475-483. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22673479/

- [5] Insights Psychology (2024). Procrastination and the Brain: A Neuroscience Guide. https://insightspsychology.org/the-neuroscience-of-procrastination/

- [6] McLean Hospital (2021). Stop Putting It Off: A Guide to Understanding Procrastination. https://www.mcleanhospital.org/essential/procrastination

- [7] Wikipedia (2025). Fear-avoidance model. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fear-avoidance_model

Government / Institutional Sources

- [8] Healthline (2021). Chronic Procrastination: Overcoming It & When to Seek Help. https://www.healthline.com/health/mental-health/chronic-procrastination

- [9] National Cancer Institute (2007). Psychological Factors Related to Delay in Consultation for Cancer Symptoms. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3320717/

- [10] Yousaf, O., et al. (2015). A systematic review of the factors associated with delays in medical and psychological help-seeking among men. Health Psychology Review, 9(2), 264-276. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26209212/

- [11] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2019). Health Care Industry Insights: Why the Use of Preventive Services Is Still Low. Preventing Chronic Disease, 16, E130. https://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2019/18_0625.htm

- [12] Institute of Medicine (2010). Missed Prevention Opportunities. The Healthcare Imperative. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK53914/

- [13] The Prevention Centre (2021). Economic benefits of prevention. https://preventioncentre.org.au/about-prevention/what-are-the-economic-benefits-of-prevention/

- [14] National Institute of Health (2005). Delays in Treatment for Mental Disorders and Health Insurance Coverage. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1361004/

Industry / Medical Sources

- [15] Koppenborg, M., & Klingsieck, K. B. (2022). Social factors of procrastination: Group work can reduce procrastination among students. Social Psychology of Education, 25(1), 249-274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-021-09682-3

- [16] PositivePsychology.com (2025). Psychology of Procrastination: 10 Worksheets & Games. https://positivepsychology.com/psychology-procrastination/

- [17] Freeman, A. T., et al. (2017). Self-Perceptions of Aging and Perceived Barriers to Care: Reasons for Health Care Delay. The Gerontologist, 57(suppl_2), S216-S226. https://academic.oup.com/gerontologist/article/57/suppl_2/S216/3913318

- [18] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2013). A Review and Analysis of Economic Models of Prevention Benefits. https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/review-analysis-economic-models-prevention-benefits-0