The most powerful medicine on Earth costs nothing, has no prescription requirements, and sits unused in 70% of the population.

Note: This article is for educational and informational purposes only. See full disclaimer at the end.

If there was a single pill that could reduce your risk of heart disease by 30%, slash your chances of depression and anxiety, slow aging at the cellular level, boost your immune system, and add years to your life—with virtually no negative side effects—would you take it every day?

That “pill” exists, and it’s called movement.

We live in an extraordinary time. Our medicine cabinets overflow with pills promising to fix everything from our hearts to our minds. Yet the most powerful medicine of all—one with virtually no negative side effects and incredible healing potential—remains dramatically underutilized.

Movement isn’t just good for you. It’s medicine. Real, measurable, life-extending medicine that works at the cellular level to prevent disease, reverse aging, and optimize every system in your body.

Why Movement Is Medicine

The evidence is overwhelming. A comprehensive analysis of nearly 100 meta-reviews involving over 128,000 participants found that physical activity is 1.5 times more effective than medication or counseling for treating depression and anxiety [1].

Regular physical activity reduces cardiovascular disease mortality by 22% to 31% when meeting minimum guidelines [2]. It literally slows aging at the cellular level, with highly active individuals showing telomeres equivalent to being nine years younger than sedentary people [3].

And perhaps most remarkably, it acts as a master regulator of your immune system, creating an anti-inflammatory environment that protects against everything from infections to cancer [4].

But here’s what the fitness industry doesn’t want you to know: you don’t need expensive equipment, extreme workouts, or perfect form to access these benefits.

You need something far more valuable—understanding how movement works as medicine and how to prescribe it for yourself.

The Reality Check: What We're Really Facing

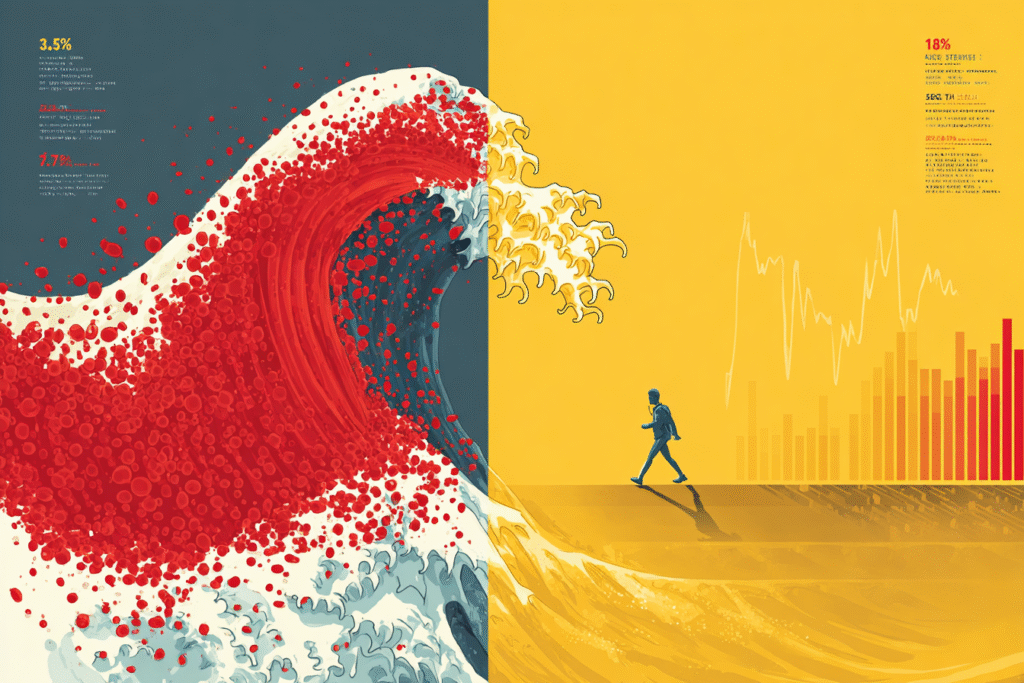

Before diving into the medicine of movement, let’s acknowledge the stark reality we’re living in. Despite having access to the most advanced healthcare in human history, we’re witnessing an alarming trend.

According to the American Heart Association’s 2024 research analysis, cardiovascular disease prevalence is expected to increase from 11.3% to 15% of the population by 2050, affecting up to 45 million U.S. adults. Stroke prevalence is predicted to double from 10 million to almost 20 million adults. Obesity, a major cardiovascular risk factor, is projected to climb from 43% to over 60% of the population [2].

We’re facing what researchers call an “oncoming tsunami of cardiometabolic disease.” The healthcare costs for cardiovascular risk factors alone are projected to triple by 2050, from $400 billion to $1.344 trillion [2].

But here’s the remarkable thing: much of this is preventable through a medicine that costs nothing, has no negative side effects when properly dosed, and is available to virtually everyone.

The Science of Movement Medicine

When you move your body, you trigger a cascade of biological responses that would make pharmaceutical companies envious. Let’s examine what happens inside your body during and after exercise, because understanding the mechanisms makes the medicine more powerful.

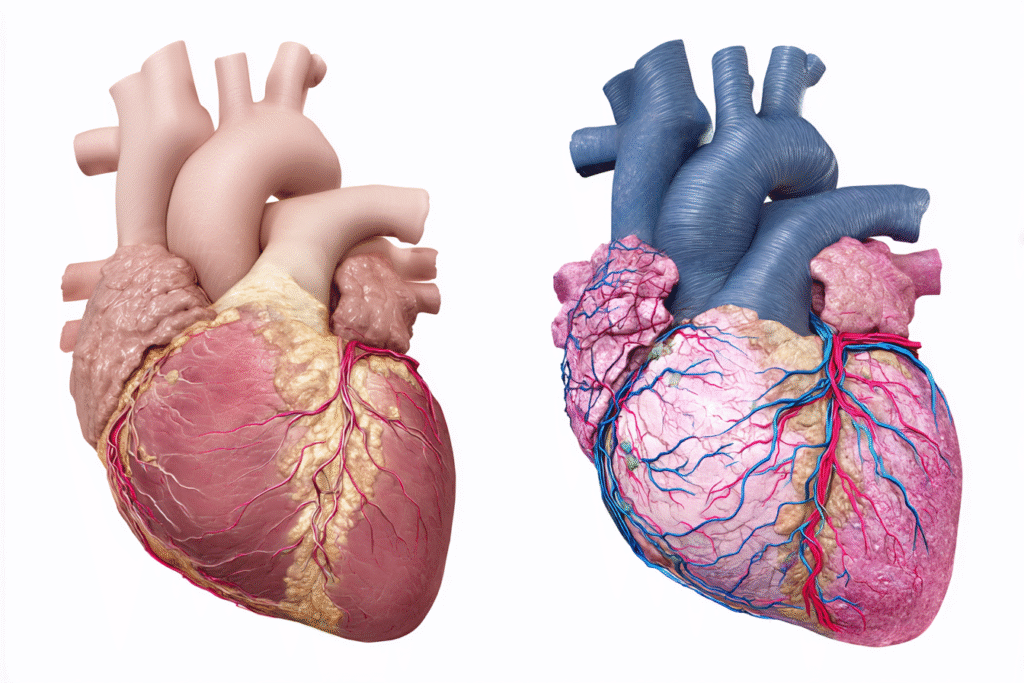

Cardiovascular Revolution

Your heart and blood vessels undergo profound adaptations with regular movement. During exercise, your heart rate increases and blood pressure temporarily rises, but these acute stresses create long-term improvements that protect against cardiovascular disease [5].

The cardiovascular benefits are extensive and measurable. Research shows regular exercise leads to lowered resting blood pressure and improved blood pressure regulation [5]. It enhances cholesterol profiles by increasing HDL (“good” cholesterol) and decreasing LDL (“bad” cholesterol) levels. Exercise dramatically improves insulin sensitivity, helping your body better regulate blood sugar. Perhaps most importantly, it increases production of nitric oxide, which helps blood vessels relax and improves circulation throughout your body [5].

Just as critically, exercise stimulates the growth of new blood vessels through a process called angiogenesis, creating a richer network to supply your organs with oxygen and nutrients. This is why exercise is so effective for people with heart disease—it helps the body create natural bypasses around blocked arteries [6].

When you exercise, your brain becomes a pharmacy, producing a cocktail of beneficial chemicals that no pill can replicate. The most famous are endorphins, your body’s natural painkillers and mood elevators. But the brain benefits go far deeper [7].

Exercise dramatically increases production of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a protein that acts like fertilizer for your brain cells. BDNF promotes the growth of new neurons and the connections between them, literally helping your brain rewire itself for better function. This neuroplasticity is why exercise is so effective for learning, memory, and cognitive performance [7].

Regular movement also optimizes the production of crucial neurotransmitters. This includes serotonin for mood regulation, dopamine for motivation and focus, norepinephrine for attention and arousal, and GABA for stress reduction and anxiety management. These neurochemical changes explain why aerobic exercise can be as effective as antidepressant medications for treating mild to moderate depression [8].

Cellular Anti-Aging Effects

At the cellular level, exercise acts as a powerful anti-aging intervention. One of the most fascinating discoveries is exercise’s effect on telomeres—the protective caps on chromosomes that shorten as we age. A landmark study found that people with consistently high levels of physical activity have telomeres that are 140 base pairs longer than sedentary individuals, equivalent to being about nine years younger at the cellular level [3].

Exercise also promotes autophagy, your body’s cellular cleaning process that removes damaged proteins and organelles. It enhances mitochondrial function, improving your cells’ energy production capacity. Additionally, regular physical activity stimulates the production of antioxidant enzymes that protect against cellular damage from oxidative stress [9]. These combined effects help explain why physically active people age more slowly and maintain better health throughout their lifespan.

Immune System Optimization

Perhaps most remarkably, exercise acts as an immune system regulator. While a single intense workout temporarily suppresses immunity, regular moderate exercise creates a powerful anti-inflammatory environment in your body.

Exercise modulates cytokine production, increasing anti-inflammatory signals while reducing pro-inflammatory ones. It enhances the circulation of immune cells, helping them patrol your body more effectively. And it reduces chronic inflammation, which underlies most age-related diseases [11].

The immune benefits are so profound that regular exercisers have lower rates of infections, better vaccine responses, and reduced risk of autoimmune diseases.

The Four-Pillar Exercise Prescription

Understanding exercise as medicine means we need to think about it like a prescription. Different types of movement provide different therapeutic benefits, and the key is creating a comprehensive approach that addresses all aspects of health.

Pillar 1: Cardiovascular Medicine

This is your heart’s prescription. Cardiovascular exercise strengthens your heart muscle, improves circulation, and provides the foundation for metabolic health.

The Prescription: 150-300 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity per week, or 75-150 minutes of vigorous-intensity activity, as recommended by the World Health Organization [10]. This translates to about 30 minutes of moderate activity five days per week, or 15 minutes of vigorous activity five days per week. Activities include brisk walking, cycling, swimming, dancing, or any movement that noticeably increases your heart rate and breathing.

The Medicine: Improved heart function, lowered blood pressure, better cholesterol profiles, enhanced insulin sensitivity, increased lung capacity, and improved circulation to all organs.

Implementation: Start with 10-15 minutes of brisk walking daily if you’re sedentary. Progress gradually. The key is consistency over intensity—moderate activity done regularly provides more health benefits than occasional intense workouts.

Pillar 2: Strength Medicine

Resistance training is medicine for your muscles, bones, and metabolism. As we age, we naturally lose muscle mass and bone density, but strength training reverses this process.

The Prescription: Muscle-strengthening activities on 2 or more days per week, targeting all major muscle groups—legs, hips, back, abdomen, chest, shoulders, and arms [12].

The Medicine: Increased muscle mass and strength, improved bone density, enhanced metabolic rate, better blood sugar control, improved functional capacity for daily activities, and reduced risk of falls and fractures.

Implementation: Start with bodyweight exercises like squats, push-ups, and planks. Progress to resistance bands or weights as you build capacity. Focus on proper form over heavy weight.

Pillar 3: Flexibility and Mobility Medicine

This pillar maintains your body’s range of motion and functional capacity. Flexibility and mobility work prevents injury, reduces pain, and maintains independence as you age.

The Prescription: Regular stretching and mobility work, ideally daily for 10-15 minutes.

The Medicine: Improved joint health, reduced muscle tension, better posture, decreased injury risk, enhanced athletic performance, and reduced chronic pain.

Implementation: Include dynamic stretching before exercise and static stretching afterward. Consider yoga, tai chi, or dedicated mobility routines.

Pillar 4: Balance and Coordination Medicine

Often overlooked, balance and coordination training becomes increasingly important as we age. It prevents falls, maintains cognitive function, and enhances overall quality of life.

The Prescription: Balance and coordination exercises 2-3 times per week, especially important for adults over 65.

The Medicine: Reduced fall risk, improved proprioception, enhanced cognitive function, better athletic performance, and maintained independence.

Implementation: Simple exercises like standing on one foot, walking heel-to-toe, or using a balance board. Many activities like dancing, martial arts, and sports naturally incorporate balance training.

Finding Your Movement Medicine Sweet Spot

Like any medicine, exercise requires proper dosing. Too little provides minimal benefits. Too much can cause harm. The key is finding your individual sweet spot—the amount that maximizes benefits while minimizing risks.

The Minimum Effective Dose

For those just starting, the minimum effective dose might be:

- 10-15 minutes of daily walking

- 2 brief strength training sessions per week

- 5-10 minutes of daily stretching

Research shows that even small amounts of movement provide substantial health benefits. A major study involving nearly 17,000 adults found that taking about 8,000 steps per day reduced mortality from any cause by 51% compared to taking only 4,000 steps per day [2].

The Optimal Range

For maximum health benefits, research supports:

- 150-300 minutes of moderate aerobic activity per week

- 2-3 strength training sessions targeting all muscle groups

- Daily flexibility and mobility work

- Regular balance and coordination practice

Avoiding Overuse

More isn’t always better. Excessive exercise can lead to overtraining syndrome, increased injury risk, compromised immune function, and burnout. Warning signs include persistent fatigue, declining performance, frequent injuries, mood changes, and sleep disruption.

Personalizing Your Movement Medicine

Just as medical treatments are personalized based on individual needs, your movement prescription should be tailored to your unique circumstances, goals, and limitations.

Based on Health Status

For Healthy Adults: Focus on maintaining and improving fitness across all four pillars. Emphasize variety and progression.

For Chronic Conditions: Exercise is medicine for most chronic diseases, but requires modification. Those with heart disease, diabetes, arthritis, or other conditions should work with healthcare providers to develop safe, effective programs.

For Injury Recovery: Movement is often the best medicine for injury recovery, but requires careful progression and sometimes professional guidance.

Based on Age

Young Adults (20s-30s): Establish lifelong habits. Emphasize skill development, strength building, and creating a broad fitness base.

Middle Age (40s-50s): Focus on maintaining muscle mass, bone density, and cardiovascular health. Begin emphasizing injury prevention and recovery.

Older Adults (60+): Prioritize functional movement, balance, and maintaining independence. Strength training becomes even more critical.

Based on Goals

Disease Prevention: Moderate, consistent activity across all pillars.

Weight Management: Combine cardiovascular exercise with strength training. Include high-intensity intervals.

Mental Health: Regular moderate aerobic exercise, especially outdoors. Include mind-body practices like yoga or tai chi.

Performance: Sport-specific training with periodization and recovery protocols.

The Anti-Inflammatory Revolution

One of the most powerful aspects of exercise as medicine is its anti-inflammatory effects. Chronic inflammation underlies most age-related diseases, from heart disease and diabetes to cancer and Alzheimer’s. Exercise is one of the most effective interventions for controlling inflammation.

During exercise, your muscles release signaling molecules called myokines. These act as anti-inflammatory agents, reducing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines while increasing anti-inflammatory ones [4]. This creates a systemic anti-inflammatory environment that protects against disease.

The anti-inflammatory effects of exercise help explain why physically active people have lower rates of cardiovascular disease, certain cancers, diabetes, autoimmune diseases, depression, and cognitive decline.

Movement Medicine for Mental Health

The mental health benefits of exercise rival those of the most effective psychiatric medications, often without the side effects. The comprehensive meta-analysis mentioned earlier found that exercise interventions were 1.5 times more effective than counseling or leading medications for managing mental health symptoms. Notably, exercise programs that were 12 weeks or shorter showed the most effectiveness, highlighting how quickly physical activity can create positive mental health changes [1].

The mechanisms include neurochemical changes (increased endorphins, serotonin, and BDNF), stress hormone regulation (normalized cortisol patterns), improved sleep quality, enhanced self-efficacy and confidence, social connection opportunities, and mindfulness and present-moment awareness.

For mental health, the prescription is clear: regular moderate exercise, especially aerobic activity, with outdoor exercise providing additional benefits through exposure to nature and sunlight.

Overcoming Common Barriers

Despite the overwhelming evidence, many people struggle to maintain regular exercise. Understanding and addressing common barriers is crucial for long-term success.

“I Don’t Have Time”

This is the most common barrier, but it’s often a perception problem. Exercise doesn’t require large time blocks. Short bouts of activity throughout the day are equally effective. Even 10-minute walks provide benefits.

Solution: Start with 10 minutes daily. Use active transportation. Include family members in physical activities. Schedule exercise like any important appointment.

“I’m Too Out of Shape to Start”

This creates a vicious cycle where inactivity leads to declining fitness, making exercise seem more daunting.

Solution: Start incredibly small. Even chair exercises or walking to the mailbox is progress. Focus on consistency over intensity. Celebrate small victories.

“Exercise is Boring”

If you find exercise boring, you haven’t found the right activities yet.

Solution: Try different activities until you find ones you enjoy. Include social elements. Listen to music, podcasts, or audiobooks. Vary your routine regularly.

“I’m Too Old to Start”

It’s never too late to start exercising. Research shows that even people in their 80s and 90s can build muscle and improve function with appropriate exercise.

Solution: Start with gentle activities like walking or chair exercises. Work with healthcare providers or qualified trainers who understand aging. Focus on functional improvements.

The Compound Effects of Consistency

The true power of movement medicine lies not in single sessions but in the compound effects of consistency. Each exercise session is like making a deposit in your health bank account, with interest that compounds over time.

Within weeks of starting regular exercise, you’ll notice improved energy, better sleep, enhanced mood, and increased strength. Within months, you’ll see significant improvements in cardiovascular fitness, body composition, and overall health markers. Within years, you’ll have dramatically reduced your risk of chronic diseases and likely added years to your life.

The key is thinking long-term. Exercise isn’t a quick fix—it’s a lifelong practice that provides cumulative benefits. The person who walks 30 minutes a day for 20 years may be healthier at 70 than someone who was sedentary until 50 and then started exercising intensely.

Creating Your Movement Medicine Plan

Here’s how to create your personalized movement medicine prescription:

Step 1: Assess Your Current State Honestly evaluate your current activity level, health status, and any limitations. Consider getting a basic health screening if you’ve been sedentary for some time.

Step 2: Set Realistic Goals Start with process goals (walk 15 minutes daily) rather than outcome goals (lose 20 pounds). Make goals specific, measurable, and time-bound.

Step 3: Choose Activities You Enjoy The best exercise is the one you’ll actually do. Try different activities until you find ones you look forward to.

Step 4: Start Small and Progress Gradually Begin with less than you think you can do. It’s better to succeed at a small goal than fail at an ambitious one. Increase gradually—about 10% per week is a good rule.

Step 5: Address All Four Pillars Ensure your plan includes cardiovascular, strength, flexibility, and balance components. You don’t need to do everything every day, but address all areas regularly.

Step 6: Plan for Obstacles Identify potential barriers and create solutions in advance. Have backup plans for bad weather, busy schedules, or equipment failures.

Step 7: Track and Adjust Monitor your progress and how you feel. Adjust your plan based on what’s working and what isn’t. Be flexible and willing to modify your approach.

The Future of Exercise Medicine

We’re entering an exciting era where exercise is being recognized as legitimate medicine. Healthcare providers are increasingly prescribing exercise for various conditions. Researchers are working to identify the optimal “doses” of different types of exercise for specific health outcomes.

Technology is making it easier to track and optimize exercise, from wearable devices that monitor heart rate variability to apps that provide personalized training programs. The future may include genetic testing to determine individual responses to different types of exercise.

But the fundamental truth remains simple: regular movement is the closest thing we have to a miracle drug. It prevents and treats more diseases, with fewer side effects, than any pharmaceutical ever created.

Your Daily Dose of Medicine

As you finish reading this, your body is waiting. Every cell, every organ system, every biological process that keeps you alive and healthy is ready to respond to the medicine of movement.

You don’t need to climb mountains or run marathons. You don’t need expensive equipment or perfect technique. You need to move your body regularly, consistently, and progressively.

Start today. Start small. Start where you are, with what you have.

Your future self—healthier, stronger, more energetic, and more resilient—is waiting.

The prescription is simple: move more, sit less, and treat exercise like the powerful medicine it is. Your body will thank you for the rest of your life.

Daily Practice: Choose one small movement you can do right now—even if it’s just standing up and stretching for 30 seconds. Movement medicine begins with a single step.

Your body is the pharmacy. Movement is the prescription. Clarity is the outcome.

See you in the next insight.

Comprehensive Medical Disclaimer: The insights, frameworks, and recommendations shared in this article are for educational and informational purposes only. They represent a synthesis of research, technology applications, and personal optimization strategies, not medical advice. Individual health needs vary significantly, and what works for one person may not be appropriate for another. Always consult with qualified healthcare professionals before making any significant changes to your lifestyle, nutrition, exercise routine, supplement regimen, or medical treatments. This content does not replace professional medical diagnosis, treatment, or care. If you have specific health concerns or conditions, seek guidance from licensed healthcare practitioners familiar with your individual circumstances.

References

To aid interpretation, references are annotated by source type. Academic sources form the core evidence base, while institutional and industry perspectives offer supplementary insights.

Peer-Reviewed / Academic Sources

- [1] Noetel, M., et al. (2024). Effect of exercise for depression: systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ, 384:e075847. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38355154/

- [2] American Medical Association. (2024). Massive study uncovers how much exercise is needed to live longer. AMA. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/public-health/massive-study-uncovers-how-much-exercise-needed-live-longer

- [3] Brigham Young University. (2017). High levels of exercise linked to nine years of less aging at the cellular level. ScienceDaily. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2017/05/170510115211.htm

- [4] Ostrowski, K., et al. (1999). Pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine balance in strenuous exercise in humans. Journal of Physiology, 515(1), 287-291. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2269132/

- [5] Nystoriak, M.A., & Bhatnagar, A. (2018). Cardiovascular Effects and Benefits of Exercise. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine, 5, 135. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6172294/

- [6] Pinckard, K., Baskin, K.K., & Stanford, K.I. (2019). Effects of Exercise to Improve Cardiovascular Health. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine, 6, 69. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6557987/

- [7] Mandolesi, L., et al. (2018). Effects of Physical Exercise on Cognitive Functioning and Wellbeing: Biological and Psychological Benefits. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 509. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5934999/

- [8] Kandola, A., et al. (2025). Physical exercise and neuroplasticity in neurodegenerative disorders: a comprehensive review. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 14, 1502417. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/neuroscience/articles/10.3389/fnins.2025.1502417/full

Government / Institutional Sources

- [9] University of California San Francisco. (2013). Lifestyle Changes May Lengthen Telomeres, A Measure of Cell Aging. UCSF News. https://www.ucsf.edu/news/2013/09/108886/lifestyle-changes-may-lengthen-telomeres-measure-cell-aging

- [10] World Health Organization. (2024). Physical activity. WHO Fact Sheet. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/physical-activity

Industry / Technology Sources

- [11] Harvard Health Publishing. (2025). Tips to leverage neuroplasticity to maintain cognitive fitness as you age. Harvard Health. https://www.health.harvard.edu/mind-and-mood/tips-to-leverage-neuroplasticity-to-maintain-cognitive-fitness-as-you-age

- [12] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). Adult Activity: An Overview. CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/physical-activity-basics/guidelines/adults.html