The most devastating bill you’ll ever pay might not come from a hospital. It might come from everything you didn’t do in time to avoid it.

Note: This article is for educational and informational purposes only. See full disclaimer at the end.

When we examined health avoidance psychology in our last article, we uncovered the Four Mechanisms that keep intelligent people waiting until crisis.

Today, we’re putting a price tag on that waiting. Not just the obvious medical bills, but the hidden cascade of costs that compound when we defer what we know we should do.

The mathematics of health avoidance are brutal. And understanding them changes everything about how we approach our wellbeing.

The Economic Architecture of Avoidance

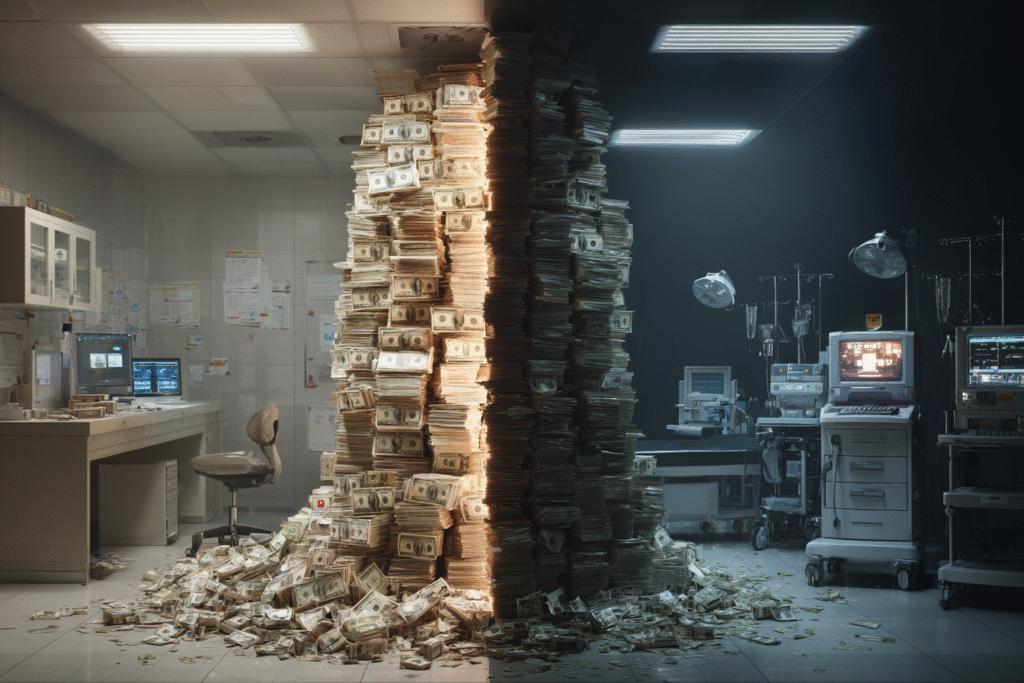

There’s a number that keeps healthcare economists awake at night: 90% of America’s $4.5 trillion annual healthcare expenditure goes toward treating people with chronic and mental health conditions [1]. These aren’t mysterious ailments that strike randomly—they’re largely preventable conditions that develop while we’re avoiding the very care that could prevent them.

The prevention paradox is stark. We spend only 3% of our healthcare dollars on prevention, while pouring 90% into treating the consequences of what we didn’t prevent [2]. It’s like having a massive leak in your roof and spending all your money on buckets while ignoring the cost of a simple repair.

Consider the direct costs that flow from this misallocation:

- Heart disease and stroke: $254 billion annually in medical costs, plus $168 billion in lost productivity [3]

- Diabetes: $413 billion in 2022 medical costs and productivity losses [4]

- Cancer care: $190 billion in annual medical costs, with growing survivorship expenses [5]

- Obesity: $173 billion per year in healthcare costs alone [6]

But here’s what makes these numbers devastating: most of these conditions are preventable or manageable with early intervention.

We’re not paying to treat the inevitable—we’re paying premium prices for what we chose to ignore.

The Emergency Room Economics

The most visible manifestation of delayed care economics plays out in emergency departments across the country. When preventive care becomes inaccessible or avoided, people without adequate primary care access are 2.5 times more likely to use emergency rooms for conditions that could have been managed in routine office visits [7].

The mathematics are unforgiving. An emergency room visit costs approximately 10 times more than the same care delivered in a primary care setting [8]. But that 10x multiplier is just the beginning. When prevention is skipped and crisis strikes, the expenses compound across every stage of care through multiple channels:

- Immediate costs increase exponentially: Emergency surgery vs. planned procedures, ICU stays vs. outpatient management

- Treatment complexity escalates: Multiple specialists vs. coordinated primary care, extended recovery periods vs. brief interventions

- Follow-up care intensifies: Lifelong chronic disease management vs. occasional monitoring

What was preventable now demands lifelong management across decades.

The cost differential between prevention and treatment is stark: while colorectal cancer screening is highly cost-effective, late-stage colorectal cancer treatment requires intensive medical intervention with significantly higher costs [9].

This dramatic difference represents the gap between simple preventive procedures and life-altering medical battles.

The Hidden Productivity Hemorrhage

While direct medical costs grab headlines, the hidden productivity losses often exceed them. This is where the true cost of health avoidance becomes staggering—lost capacity stretches across entire careers, quietly eroding energy, focus, and momentum over time.

Employees with chronic conditions experience 25-50% reduced productivity while at work, a phenomenon researchers call “presenteeism” [10]. They’re physically present but cognitively and physically compromised. In team-based work environments, this creates a multiplier effect—when key employees are absent for health reasons, the cost to employers increases by 1.6 times their daily wage due to disrupted collaboration and knowledge gaps [11].

The career trajectory impact extends far beyond immediate productivity losses:

- Health-related performance decline can derail promotions and reduce earning potential

- Early retirement often becomes necessary due to chronic health conditions

- Hiring discrimination occurs as companies avoid employees with health risks

- Insurance premium increases of 15-20% affect companies with unhealthy workforces [12]

The scale becomes clear when we examine broader economic data. The global economic burden of mental illness alone was $2.5 trillion in 2010, projected to reach $6.1 trillion by 2030—with most of this burden attributed to lost productivity rather than direct medical costs [13].

The Relationship Cost Cascade

Health crises don’t exist in isolation—they create financial shockwaves through entire family systems. Medical bankruptcy remains a leading cause of personal financial collapse, but the relationship costs are often more devastating and harder to quantify.

Family members frequently reduce work hours or quit jobs entirely to provide care, creating what economists call the “caregiver tax.” The financial pressure from mounting medical costs strains marriages and family relationships, while children in families dealing with preventable health crises experience educational disruption and reduced opportunities.

When preventable health issues become chronic conditions, they create cascading financial impacts:

- Multi-decade financial drains that consume retirement savings

- Reduced inheritance potential as medical costs deplete family wealth

- Generational impact affecting children’s educational and career opportunities

- Insurance complications that can affect entire family coverage

The social isolation compounds both health and economic problems. Chronic health conditions limit participation in professional and social networks, while friends and extended family experience emotional strain and caregiver fatigue as support demands escalate.

Professional relationships suffer as health-related absences and reduced performance damage career opportunities and earning potential.

The Time Debt You Can’t Repay

Time is the only truly non-renewable resource, and health avoidance creates devastating opportunity costs that stack over time. Preventable conditions reduce physical and cognitive function earlier and more severely than necessary, limiting participation in activities that bring meaning and joy while consuming time that could be spent building relationships and pursuing goals.

The recovery time differential is particularly cruel. A preventive cardiac screening takes two hours. Recovery from a heart attack can take six to twelve months. Emergency interventions require significantly longer recovery periods than preventive measures, stealing months or years from productive, enjoyable living.

Perhaps most profound is what we steal from our future selves. Preventable conditions shorten healthy lifespan and reduce retirement enjoyment. While Medicare covers basic care, chronic condition management often requires significant out-of-pocket expenses that consume retirement savings. Many preventable conditions lead to earlier need for assisted living or nursing care, transforming potential inheritance into medical debt.

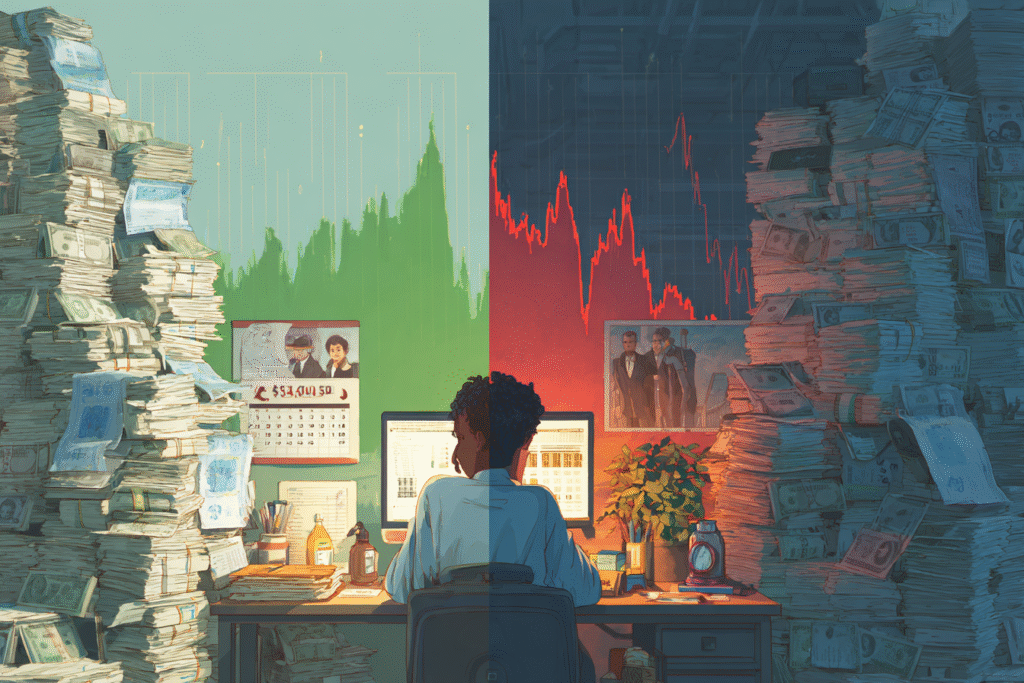

The Psychological Accounting Error

Our brains systematically fail at health economics through what behavioral economists call “present bias”—we overvalue immediate costs while undervaluing future consequences. This creates a devastating error in health decision-making that costs Americans trillions annually.

We’ll avoid a $500 preventive procedure due to immediate financial impact, then somehow find ways to pay for a $50,000 emergency intervention. The math makes no sense, but the psychology is powerful.

We treat preventive costs as certain and immediate. We treat future health costs as uncertain and distant. But in reality, the opposite is often true.

We’ve become experts at rationalization, telling ourselves stories that make economic sense individually but create financial catastrophe collectively:

- “I can’t afford it right now” (while spending money on less important things)

- “I don’t have time” (while spending hours on activities that provide less value)

- “I’ll deal with it when it becomes a problem” (not realizing it’s already a bigger problem to wait)

- “My insurance doesn’t cover it” (ignoring that emergency treatment costs far more)

Each rationalization protects us psychologically while bankrupting us financially.

But what happens when we correct these psychological errors and approach health with the same financial intelligence we apply to other investments?

The numbers become transformative.

The Prevention Investment Framework

When we shift from crisis intervention economics to prevention investment thinking, the return on investment becomes compelling:

- Daily aspirin use: Cost-effective at less than $5,000 per quality-adjusted life year saved [14]

- Blood pressure management: Returns $3-4 for every dollar invested [15]

- Diabetes prevention programs: Reduce healthcare costs by 50% while improving quality of life [16]

- Cancer screening: Early detection significantly reduces treatment complexity and costs [17]

This represents the compound interest of health—a dollar spent on prevention in your thirties can save $10-20 in healthcare costs in your sixties. Yet most people track their financial investments religiously while ignoring their health investments entirely.

Companies that invest in comprehensive preventive care see 25-30% reductions in total healthcare costs [18]. Wellness programs with proper implementation return $3-6 for every dollar invested [19]. The evidence is overwhelming: prevention isn’t an expense—it’s the highest-return investment available.

The Systems Solution

The solution requires both individual behavior change and systemic reframing of health economics. Value-based care models that reward prevention over treatment volume, insurance coverage policies that make preventive care more accessible than crisis intervention, and personal systems like health savings accounts that incentivize prevention over treatment.

At the individual level, this means creating annual health maintenance budgets separate from crisis intervention funds, tracking prevention ROI as carefully as financial investments, and treating early intervention as preventing compound interest on health debt.

Smart health investing requires the same discipline as financial investing: regular contributions, long-term thinking, and measuring results over time rather than seeking immediate returns.

Tomorrow's Promise

Understanding the true cost of waiting changes everything. When we see health avoidance not as saving money but as accumulating compound debt, our decision-making shifts fundamentally.

The four psychological mechanisms we explored yesterday—Fear Amplification, Emotional Overwhelm, Control Illusion, and Expertise Intimidation—create real financial consequences measured in hundreds of thousands of dollars over a lifetime. But they’re not inevitable. They’re habits of thinking that can be changed with better systems.

Tomorrow, we’ll begin building those systems. We’ll explore how to build a simple personal health protocol—one that gives you clarity, early warning signs, and actionable momentum before anything becomes a crisis.

The economics are clear: prevention isn’t an expense—it’s the highest-return investment you can make. The question isn’t whether you can afford to take care of your health. The question is whether you can afford not to.

You don’t need to overhaul your entire life to avoid catastrophe. But you do need to stop treating health like a negotiable expense. A small step today can be the difference between a routine checkup—and a decade-long battle you never saw coming.

See you in the next insight.

Comprehensive Medical Disclaimer: The insights, frameworks, and recommendations shared in this article are for educational and informational purposes only. They represent a synthesis of research, technology applications, and personal optimization strategies, not medical advice. Individual health needs vary significantly, and what works for one person may not be appropriate for another. Always consult with qualified healthcare professionals before making any significant changes to your lifestyle, nutrition, exercise routine, supplement regimen, or medical treatments. This content does not replace professional medical diagnosis, treatment, or care. If you have specific health concerns or conditions, seek guidance from licensed healthcare practitioners familiar with your individual circumstances.

References

The references below are organized by study type. Peer-reviewed research provides the primary evidence base, while systematic reviews synthesize findings across multiple studies for broader perspective.

Peer-Reviewed / Academic Sources

- [1] Buttorff, C., Ruder, T., & Bauman, M. (2017). Multiple Chronic Conditions in the United States. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/tools/TL221.html

- [2] Woolf, S. H. (2010). Missed Prevention Opportunities – The Healthcare Imperative. National Academies Press. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK53914/

- [3] Tsao, C. W., Aday, A. W., Almarzooq, Z. I., et al. (2023). Heart disease and stroke statistics—2023 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 147(8), e93–e621. https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001123

- [4] Parker, E. D., Lin, J., Mahoney, T., et al. (2024). Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. in 2022. Diabetes Care, 47(1), 26-43. https://diabetesjournals.org/care/article/47/1/26/153797/Economic-Costs-of-Diabetes-in-the-U-S-in-2022

- [5] Mariotto, A. B., Enewold, L., Zhao, J., et al. (2020). Medical care costs associated with cancer survivorship in the United States. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 29(7), 1304–1312. https://aacrjournals.org/cebp/article/29/7/1304/72361/Medical-Care-Costs-Associated-with-Cancer

- [6] Ward, Z. J., Bleich, S. N., Long, M. W., & Gortmaker, S. L. (2021). Association of body mass index with health care expenditures in the United States by age and sex. PLoS One, 16(3):e0247307. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0247307

- [7] Udalova, V., Powers, D., Robinson, S., & Notter, I. (2022). Most vulnerable more likely to depend on emergency rooms for preventable care. U.S. Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2022/01/who-makes-more-preventable-visits-to-emergency-rooms.html

- [8] UnitedHealth Group. (2019). The High Cost of Avoidable Hospital Emergency Department Visits. https://www.unitedhealthgroup.com/newsroom/posts/2019-07-22-high-cost-emergency-department-visits.html

- [9] Mariotto, A. B., Yabroff, K. R., Shao, Y., et al. (2011). Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010-2020. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 103(2), 117-128. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3107566/

Government / Institutional Sources

- [10] Loeppke, R., Taitel, M., Haufle, V., et al. (2009). Health and productivity as a business strategy: a multiemployer study. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 51(4), 411-428. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19339899/

- [11] Nicholson, S., Pauly, M. V., Polsky, D., et al. (2006). Measuring the effects of work loss on productivity with team production. Health Economics, 15(2), 111-123. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/hec.1052

- [12] Baicker, K., Cutler, D., & Song, Z. (2010). Workplace wellness programs can generate savings. Health Affairs, 29(2), 304-311. https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0626

- [13] Bloom, D. E., Cafiero, E. T., Jané-Llopis, E., et al. (2011). The Global Economic Burden of Noncommunicable Diseases. World Economic Forum and Harvard School of Public Health. https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Harvard_HE_GlobalEconomicBurdenNonCommunicableDiseases_2011.pdf

Industry / Technology Sources

- [14] Cohen, J. T., Neumann, P. J., & Weinstein, M. C. (2008). Does preventive care save money? Health economics and the presidential candidates. New England Journal of Medicine, 358(7), 661-663. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp0708558

- [15] Russell, L. B. (2009). Preventing chronic disease: an important investment, but don’t count on cost savings. Health Affairs, 28(1), 42-45. https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.42

- [16] Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. (2012). The 10-year cost-effectiveness of lifestyle intervention or metformin for diabetes prevention. Diabetes Care, 35(4), 723-730. https://diabetesjournals.org/care/article/35/4/723/38335/The-10-Year-Cost-Effectiveness-of-Lifestyle

- [17] National Cancer Institute. (2023). Financial Burden of Cancer Care. https://progressreport.cancer.gov/after/economic_burden

- [18] Goetzel, R. Z., & Ozminkowski, R. J. (2008). The health and cost benefits of work site health-promotion programs. Annual Review of Public Health, 29, 303-323. https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090930

- [19] Harvard Business Review. (2004). Presenteeism: At Work—But Out of It. https://hbr.org/2004/10/presenteeism-at-work-but-out-of-it